Completing the NYMC Triathlon: Three Alums with Three Degrees

Earning a Doctor of Medicine degree is hard. Mix in a Master of Science, Master of Public Health or Doctor of Philosophy degree—or some combination thereof—and it may seem impossible

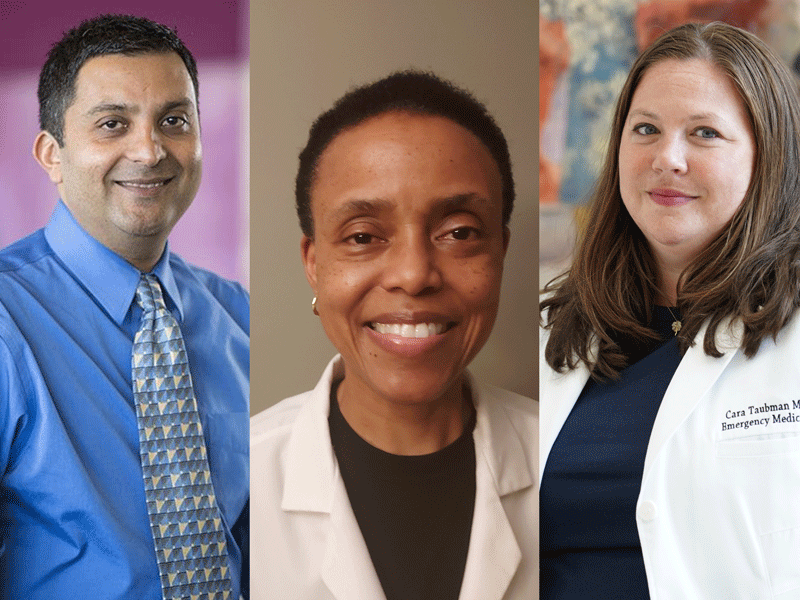

Just eight New York Medical College (NYMC) alumni are in the esteemed circle of holding a triumvirate of degrees, one from each school, the School of Medicine, the Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences and the School of Health Sciences and Practice. Chironian met up with three of them: Karen Clarke, M.S. ’93, M.P.H. ’94, M.D. ’96; Rajeer Vibhaker, Ph.D. ’99, M.P.H. ’99, M.D. ’99; and Cara Taubman, M.S. ’05, M.P.H. ’10, M.D. ’10. Though they grew up in different parts of the world and have different specialties and research interests, they all knew they wanted to become physicians in early childhood. What they didn’t know was how NYMC would open a world of possibilities to them and make those childhood dreams a reality.

Karen Clarke, M.S. ’93, M.P.H. ’94, M.D. ’96

For Dr. Clarke, there is no contradiction between science and faith. “Every morning,” she says, “I start with a prayer that all my patients will have good outcomes.” Dr. Clarke is a hospitalist at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia, as well as an associate professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine. As a hospitalist, she is the lead physician for hospitalized patients with a range of acute and chronic conditions, spanning from young adults to the elderly.

For Dr. Clarke, there is no contradiction between science and faith. “Every morning,” she says, “I start with a prayer that all my patients will have good outcomes.” Dr. Clarke is a hospitalist at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia, as well as an associate professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine. As a hospitalist, she is the lead physician for hospitalized patients with a range of acute and chronic conditions, spanning from young adults to the elderly.

In her earlier years, Dr. Clarke pictured herself in a career-oriented more towards research than clinical medicine. Growing up in the Bahamas, she was a self-described science nerd whose favorite school subjects were biology, chemistry and physics. “By the time I was eight or nine, I was thinking that I wanted to be a doctor,” she recalls. “I was encouraged by teachers and incredibly supportive parents. They expected me and my sisters to do well and made many sacrifices for us,” she notes. She went to the best schools available in the Bahamas then to high school in England.

At Nebraska Wesleyan University, she majored in chemistry and then arrived at NYMC where she earned an M.S. in microbiology and immunology, an M.P.H. in environmental health and her M.D. She completed her internal medicine internship and residency at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at San Antonio, worked in emergency care in several Texas hospitals, served as a house physician in upstate New York, and then as a hospitalist in Texas and Arizona before arriving at Emory in 2008.

“My plan in medical school was to focus more on research,” she says. “Thirty years ago, I was sure that I would be running a research lab as my career progressed— maybe even inventing new medicines. My interest was always in helping sick people get better.” Dr. Clarke has published papers addressing topics such as COVID-19 and catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Some of her publications also focused on quality improvement issues such as the appropriate use of diagnostic tests and medications (specifically proton pump inhibitors) in hospitalized patients.

Although she maintains these and other research interests, Dr. Clarke’s career trajectory shifted and, for more than 20 years, she has devoted herself primarily to hands-on patient care.

Dr. Clarke typically sees 12 to 18 patients daily, some of whom have been sent from other facilities to Emory because of its status as a tertiary care hospital. She takes particular satisfaction in attending to the smallest details and finding accurate diagnoses—something she emphasizes when teaching physician assistant students who round with her.

We should never move forward without a clear vision,” she says. “Every test and every procedure we order, every medication we administer—there has to be a solid rationale for why something should or should not be done based on the specific needs of that patient.” For relaxation, Dr. Clarke listens to music. “A little of everything,” she says, “but especially reggae and tunes of the 80s and 90s.” She loves to travel, having been to Central America, the Caribbean, many countries in western Europe and a good portion of the U.S.

Although Dr. Clarke’s professional life took a turn she did not quite expect, she knows she is in the right place. “I give every patient a hundred percent,” she says, “and I work extremely hard to keep learning from all of them. God carries me every day through every decision I make about caring for my patients. I feel blessed.”

Rajeer Vibhaker, Ph.D., ’99, M.P.H. ’99, M.D. ’99

Dr. Vibhakar pictured himself as a family doctor from the time he was a young boy in Moshi, Tanzania, making home visits with his family physician father. “I watched him interact with everyone from babies to grandmas,” he says, “and I knew that was what I wanted to do.”

Dr. Vibhakar pictured himself as a family doctor from the time he was a young boy in Moshi, Tanzania, making home visits with his family physician father. “I watched him interact with everyone from babies to grandmas,” he says, “and I knew that was what I wanted to do.”

Now, as a physician-scientist specializing in pediatric oncology—specifically childhood brain tumors—Dr. Vibhakar still cares for families but not as he originally envisioned. “Yes, I am a medical doctor,” he says. “I check lab reports and prescribe treatments. But my clinical work is taking care of the families who are navigating unfamiliar territory and often have to make difficult decisions.”

He began his academic journey at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota, where he majored in chemistry and biology. Applying to medical schools was a challenge; at that time, he was still on a foreign student visa. But NYMC allowed foreign students to apply and accepted him.

Although he had done some research in college, Dr. Vibhakar did not initially see research as his focus. However, during his first year, he was assigned to shadow Joseph M. Wu, Ph.D., professor of biochemistry and molecular biology. “He was an amazing teacher who got me excited about his work understanding how DNA binds to proteins.” Subsequently, he was accepted into the M.D./Ph.D. program specializing in pathology, where he realized that he could also fit in the classes needed for the M.P.H. specializing in epidemiology and pursued that degree as well, doing research in a cancer biology lab.

He completed his residency in pediatrics and a fellowship in pediatric oncology at the University of Iowa. In 2014, he joined the University of Colorado School of Medicine where he is currently professor of pediatrics, program leader for the Pediatric Neuro-Oncology Program and a faculty member in the Department of Neurosurgery, Department of Cell and Developmental Biology and Cancer Biology Program.

Dr. Vibhakar spends about two-thirds of his time in the lab and the remainder caring for children with brain tumors and young adults whose tumors were diagnosed earlier in childhood. He explains that pediatric brain tumors are different from those found in adults. “A pediatric tumor occurs because of dysregulation during development,” he says. “Cells replicating in a particular location that should go quiescent do not do so at the right time; they keep multiplying and develop into tumors.”

His lab studies what happens when that development goes awry. “Why the development goes wrong is almost impossible to answer at this point,” he notes. “But if we can figure out what happens when development goes wrong, we can make progress.” Dr. Vibhakar’s lab researches the basic mechanisms of how DNA is packaged and the pathways and mechanisms that cancer cells depend on that, if better understood, could be targeted for therapy.

As a clinician, Dr. Vibhakar notes that survival rates for some kinds of pediatric brain tumors have increased significantly in the past 20 years. “But there are others on which we have made no progress. So, for some patients, I am able to offer therapies and hope; for others, the conversation has to be about quality of life and end-of-life care,” he says. When he teaches, he emphasizes two skills. “First, I want them to be able to think through the problem,” he says. “My residents sometimes get upset because I will not let them just report lab results. Until you tell me why that number does or does not matter for the patient, I do not want to hear what the number is.”

The second lesson is how to listen to family members. “Sometimes parents will tell the doctors what they think we want to hear or will describe something as normal because they have become accustomed to it. Do not listen only to the words. Watch faces, gestures and tones of voices. And really listen to the children themselves. Often, they will be the ones to tell us what is really going on,” he explains.

About his career, Dr. Vibhakar says, “I love what I do. As a physician-scientist, you get calls from the clinic while you are in the lab, and you will have the lab paperwork awaiting you after your clinic time. But if you really want to make a difference, being a physician-scientist is the way to go. Even with the amount of work, I would not want to do anything else.”

Cara Taubman, M.S. ’05, M.P.H. ’10, M.D. ’10

Exposed to medicine at an early age by her mother and godmother, both nurses, Dr. Taubman found her calling when she spent a high school summer volunteering in the Emergency Department at New York’s St. Luke’s Hospital. “That summer solidified for me that I wanted to be a doctor,” she says.

Exposed to medicine at an early age by her mother and godmother, both nurses, Dr. Taubman found her calling when she spent a high school summer volunteering in the Emergency Department at New York’s St. Luke’s Hospital. “That summer solidified for me that I wanted to be a doctor,” she says.

After obtaining a B.S. in microbiology at the University of Rochester, she came to NYMC to study biochemistry. The following year, she worked with autistic children in Brooklyn while applying to medical school and then entered NYMC’s M.D./M.P.H. program.

Her summer at St. Luke’s sparked her interest in emergency medicine. However, once in medical school, Taubman told herself that she was not automatically going to focus on that field. “But, as I went through my rotations,” she says, “the problem turned out to be that I liked a little bit of everything.” So, she returned to her first love—which, she points out, does have “a bit of everything”—and went on to complete a residency in emergency medicine at Jacobi and Montefiore Medical Centers.

Since 2017, Dr. Taubman has been assistant director of the Emergency Department at New York’s Harlem Hospital, caring for fellow New Yorkers and sharing responsibility for the department’s day-to-day operations. Her path to her current position took her through Ghana, Rwanda and South Sudan as part of Columbia University’s fellowship program in global emergency medicine. For much of the two-year program, Dr. Taubman worked with Doctors Without Borders, known internationally by its French name— Médecins Sans Frontières or MSF. She developed a mass casualty plan for a hospital in Ghana, helped the Rwandan government develop and administer an assessment of acute care capacity in the country’s hospitals, taught emergency medicine and provided direct patient care in refugee and internally displaced persons camps in South Sudan.

When her fellowship was completed, Dr. Taubman knew she wanted to go back into the city hospital system. “I have always been a proud New Yorker,” she says, “and who takes care of New York? The public hospitals.”

Her experience in global emergency medicine turned out to be excellent preparation for her other role at Harlem Hospital—clinical director of emergency management—particularly when the COVID-19 pandemic took hold in New York City. Overseas, she dealt with sudden influxes of patients because of mass casualties or the rapid spread of infectious agents, where there was a tremendous amount of need, and where medical personnel had to constantly re-direct resources to help the largest number of people who needed extra care.

“That was what we faced in New York in the spring of 2020. It was a difficult and surreal time, but I was able to help my colleagues who had never been in a parallel situation,” says Dr. Taubman. “I am proud of how we handled the spring of 2020. I do not think anyone could have been prepared for what happened. But, if I had to do it again, the people at Harlem Hospital are the ones I would want to work with.” When she is not working. Dr. Taubman loves to travel, read especially nonfiction, and explore the Big Apple. She will tell you that, despite what we see on television, life in the ER is not filled with glamour and non-stop excitement. But she loves her work and points out that, as an emergency medicine physician, she feels privileged to be able to treat anyone who needs care without regard to insurance status.

“I have the greatest job in the world,” she says. “I get to care for people who may be in their worst moments and tell them they are going to be okay. I do not always get to fix them right then—sometimes my colleagues will do that. But I get to reassure them: We are here and we will help you.”